By Rajiva Wijesinha –

Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha MP

Enemies of the President’s Promise: Mahinda Rajapaksa and the Seven Dwarfs – Grumpy five

I also suggested, as occurred in Pakistan, the establishment of ordinary schools by the military, or taking more than the management of existing schools in regions where the military had a presence. This had been crucial in Pakistan, exactly where the public education technique had been inadequate in rural regions where there have been military cantonments. The army had for that reason begun schools to cater to the kids of military personnel, and these had been then opened to the public too for a fee.

Sri Lanka however, getting had a good public education program, had not initially needed such establishments while, the nation becoming modest, military personnel had not normally had their households with them when they were stationed away from Colombo, given that standard visits were achievable. But although coordinating on behalf of Sabaragamuwa University the degree programme at the Sri Lanka Military Academy in Diyatalawa, I had noticed how a lot a lot more content material have been the officers whose wives and youngsters had been with them. This was attainable only when the kids were really young, since later on it was believed important that they be admitted to excellent schools in Colombo, provided the inadequacies of rural schools. But it struck me then that the SLMA could effortlessly take charge of one or two nearby schools in Diyatalawa, something I had certainly suggested for Sabaragamuwa University and the regional college in Belihuloya, since I saw how my academic colleagues suffered from possessing to send their youngsters to schools in bigger towns.

Offered the commitment of the much more sophisticated parents who would now be sending their kids to the local school, the normal of education there would boost, to the advantage too of the regional children. And the managing institution would make sure that vital subjects, such as English and Mathematics and Science, which have been grossly neglected in a lot of rural schools, would be properly taught.

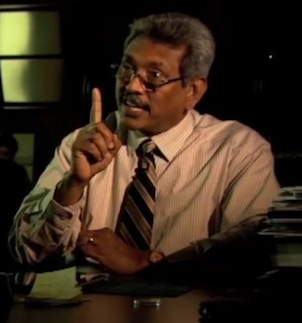

Gotabaya

The Ministry of Defence had indeed taken more than 1 college soon after the war, but this was in Colombo. But my suggestion as to this and other initiatives was not taken up, with Gotabaya laconically telling me that he would have to face even far more criticism with regard to what was described as militarism. Later nonetheless, soon after a paper I developed for a Defence Seminar, he told me to go ahead, but I explained that I could do practically nothing, it was the Kotelawala Defence University and other military bodies that had to take the lead – though the KDU, offered its civilian agenda, was uniquely positioned to move in this matter with out criticism.

I did then take up the matter with the KDU but, probably because it had to work via civilian academics in many regions, there was hardly any progress on the matter. One particular Department did produce great concepts with regard to the coaching of health-related support staff, but that alone was not adequate, and quickly I was not in a position, having protested about what happened at Weliweriya, to pursue the thought. I was put off, albeit really politely, with regard to a paper I had been asked to prepare for a symposium, and the Commandant later indicated wryly that the Secretary had not been pleased about my signing the petition.

I knew this, simply because he had in truth called me up and shouted at me for obtaining, as he put it, signed one thing along with enemies of the government. He did grant that what had happened was incorrect, but his point was that I was obtaining involved with these who had been intrinsically opposed to the government. I did not believe this was the case, and indeed I had toned down the initial draft which had thrown the blame for the incident on him almost personally, but I could understand his irritation. But I was shocked and saddened that he should have embargoed my participation in seminars organized by the military, simply because these had been amongst the most constructive in the current past, in a context in which Sri Lanka had no actual think tanks.

Indeed, just soon after the incident at Weliweriya, ahead of I signed the protest, I had presented a paper at the recently established Officer Career Development Centre at Buttala, on the website of 1 of the Affiliated University Colleges exactly where, twenty years earlier, I had coordinated the English course. I had discovered the senior officers there as worried as I was about the reality that the army had opened fire on civilians. They as well recognized how undesirable this was for their reputation, due to the fact it would lend strength to these who claimed that the forces had targeted civilians deliberately in the war against the LTTE.

My continuing belief is that the senior officers nicely understood the guidelines of war and had worked in accordance with them throughout the war. Right after the war I had personal knowledge about how positive they were about the civilians they were in charge of. For instance, 1 of the toughest generals for the duration of the war, Kamal Guneratne, who was head of the Safety Forces in Vavuniya, and accountable for the Welfare Centre exactly where the displaced population had been housed, proved astonishingly liberal about releasing the vulnerable, even even though he was told that many security checks have been essential ahead of this could be accomplished. And as noted previously, when efforts have been created to delay the resettlement Basil Rajapaksa was attempting to expedite, the generals in the field ignored the order they had received to recheck civilians and sent them back to their locations of residence as rapidly as possible.

So too it was civilians with a pluralistic outlook whom they invited to their seminar discussions. At Buttala for instance they known as on members of the LLRC, who had been typically blacklisted by the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute for International Relations and Strategic Research, which was run by the Ministry of External Affairs. Serious discussion was impossible there, whereas at both Buttala and the KDU, and the Training Centre that one more quite bright general had set up at Kilinochchi, the former capital of the LTTE, open and frank discussion was encouraged.

It was tragic then that, as time passed, Gotabhaya seemed to harden and prevent his senior officers from developing, together with liberal civilians, programmes that would have promoted reconciliation. Provided both continuing security requirements, and the comparative efficiency of the military, there was no doubt that they necessary to remain active in the North. But techniques and means could have been found of avoiding a heavy handed strategy, and promoting civilian leadership which the military could support, rather than seeming to impose itself as an independent authority. The synergy that military coaching engendered within the forces appears to have been avoided with regard to the Tamil population of the North, and the impression that Gotabaya saw them as outsiders, not folks he ought to care about as equals, became entrenched.

***

That he held related views about the Muslims had also become clear. Certainly his presentation of himself as the champion of the chauvinists crystallized by way of his association with a group that targeted the Muslims. This was the Bodhu Bala Sena, the Buddhist Strike Force, which started in 2013 to engage in a vicious and violent campaign against Muslims.

Matters came to a head in this regard when, in June 2014, right after some preliminary skirmishes, they provoked violent action against Muslims in the Aluthgama location, at the southern end of the Western Province, with the police taking neither preventive nor restraining action. Both the President and Gotabaya had been out of the country at the time, which highlighted the absurdity of a situation in which the country had an octogenarian Prime Minister with out the capacity to feel or take choices.

There had been all sorts of conflicting stories about what had occurred, which includes the claim that Gotabaya had in truth ordered the police to make sure much better control, but this had been ignored. Undoubtedly the President behaved much better than his counterpart JR Jayewardene had done in 1983 when there was violence against Tamils. But the plain reality was that the BBS had been permitted to engage in provocative rhetoric and the police had completed practically nothing to stop the rioting that followed.

The President’s responses afterwards indicated that he was in a state of confusion, and was not becoming presented with the whole picture. Firstly he claimed that some Muslims were certainly trying to take up arms, which echoed each the claim by the safety establishment that there had been efforts to start off a jihadi movement in the nation and the assertion by the BBS leader that, because some Muslim politicians have been attempting to establish a Gaza strip in Sri Lanka, they would respond like the Israelis.

Such echoes of Gotabaya’s fascination with the Israelis possibly explains why the President had not been told that Muslims in his own celebration had requested that the BBS rally be banned. He claimed that they had only gone to the affected region afterwards, but this was belied by a Muslim Minister in whom he had wonderful trust, who confirmed that his plea had been ignored.

Second, the President granted that, regardless of the Muslim extremism he alleged, the BBS was a dangerous organization, but claimed that it was funded by the Americans and the Norwegians to destabilize the government. Certainly it was accurate that BBS personnel had, before the movement was set up, received some Norwegian funding, but it was also true that they had been patronized by the Secretary of Defence. The President claimed that Gotabaya had only attended a meeting at which the BBS was present at his request, but that did not explain why what Gotabaya said seemed to echo the chauvinist sentiments of the BBS. And it was at odds with the claim of the BBS leader that it was the Norwegian they have been associated with, a shadowy figure the Embassy, which was a lot more transparent in its activities, need to have been wary about, who had asked that Gotabaya be invited as the Chief Guest. The President surely had no answer to the question why, if the Americans were engaged in a programme aimed at weakening the government, Gotabaya so readily fell into their trap.

Despite his criticism of the BBS, the President insisted that he could take no action, since he thought the Buddhist clergy would protest. This was nonsense, due to the fact several top Buddhist monks had spoken out against the BBS. It was also nonsense to claim that he would be accused of being a dictator if he were firm, offered that it was precisely those who felt that civil liberties were becoming eroded who urged making use of the complete force of the law against the violent agenda of the BBS.

But, assuming that the President was not himself involved in the move to heighten tensions, it seemed clear that he felt himself straitjacketed. Given that he seemed convinced that it was only hardliners he could rely on electorally, he was clearly not going to take action against such extremists with elections due quickly. And doubtless he would be held to this position, given that Gotabaya had announced an intention to enter politics, combining this with the assertion that he would do considerably much better than current politicians. So, although he couched this apparent modify of thoughts in terms of willingness to satisfy a request of the President, if he made 1, he was creating no bones about the truth that he subscribed to the mythology of his outstanding capacities.