By Izeth Hussain –

Izeth Hussain

A number of concerns arose in my mind whilst reading the opening paragraphs of K.M. de Silva’s Sri Lanka and the Defeat of the LTTE (2012). In May possibly 1987 the armed forces led by Common Cyril Ranatunge routed the LTTE at Vadamarachchi, and Prabhakaran together with some of his best associates fled in disarray to Tamil Nadu where they had been accommodated by the regional government. Basic Ranatunge had planned to proceed thereafter to Jaffna town and its environs, but he desisted on the orders of President JR Jayewardene. The purpose for the President’s decision was that he had been warned by the Indian Government that the military move into Jaffna would be resisted by the Tamils, resulting inevitably in a blood bath and that would be unacceptable to India. The Indian Government took up that position due to the fact of pressure from Tamil Nadu.

The author points out that it took twenty two much more years to comprehensive what Common Ranatunge had begun. “Those of us who knew what had occurred were disappointed at the consequences of this Indian intervention but always felt that the LTTE could be defeated militarily ….” There followed the years and decades during which the defeatist notion prevailed that the war was unwinnable. “General Ranatunge’s Vadamarachchi campaign was one particular of the forgotten episodes of the struggle against the LTTE, forgotten by the politicians in Sri Lanka, such as heads of government”. In his retirement he would speak about the accomplishment of the Vadamarachchi campaign to guests, “especially those whom he trusted to be discreet …..”. Common Sarath Fonseka, who was a lieutenant colonel in the Vadamarachchi operation, knew that the war was winnable and proceeded to win it in 2009.

Briefing the President of the intended Vadamarachchi battle program

We have to ask no matter whether the Indian Government was justified in demanding that the armed forces desist from going into Jaffna, and regardless of whether President Jayewardene was justified in providing in to that demand. The distinct question that arises in that connection is whether or not there was anything untoward in the Vadamarachchi operation, something that went against the established norms of war, something that in any way outraged the moral sensibility of the international neighborhood. The issue of food shortages in Jaffna was significantly bruited about in the weeks preceding the air-drop of 1987. In the course of that period I was second-in-command at the Foreign Workplace, and I recall a considerable exchange that I had with Higher Commissioner Dixit when he met me on a matter that had nothing to do with the ethnic difficulty. Soon after finishing with that matter, I asked him what really was the food predicament in the North. He began his reply with a statement that surprised me. It went anything like this:”I am glad that at last somebody has asked me that question”. It signified a serious failure in communication among the two Governments. He went on to say that at the moment men and women in Jaffna ate only 1 meal a day, which was inadequate for human sustenance, and sooner or later 1 or much more persons would die of hunger. When that occurred all hell would break loose in Tamil Nadu, and the Delhi Government would find itself in a hard position.

Even so, none of that happened and the Government was not accused of utilizing starvation of Tamil civilians as a weapon of war against the LTTE to any severe extent, which would have been regarded as morally reprehensible by the international neighborhood. There definitely have been meals shortages in the North but that was not a aspect in the military operations that decided the outcome at Vadamarachchi. Moreover there were no allegations of war crimes as in 2009. What took place in Vadamarachchi in 1987 was a simple military operation illustrating one of the basics of guerilla warfare: guerilla forces can not win against Government troops in positional warfare except at the final stages right after demoralization has gone far among the government troops and they begin operating, as in Vietnam in 1975.

So, taking count of prevailing international norms, nothing at all ought to have precluded General Ranatunge proceeding to Jaffna and ending the LTTE rebellion after and for all. We should bear in mind, above all, that the State has the primordial duty of placing down armed rebellion as otherwise it loses its quite raison d’être: according to Weber’s definition the State legitimizes itself by getting a monopoly of the indicates of violence. So why did the Indian Government demand that our troops desist from going into Jaffna and why did President JR succumb to that demand? Numerous Sri Lankans, possibly most, will hold that it was a case of Indian imperialist bullying of a modest neighbor. I hold that the explanation is that Rajiv Gandhi believed that he could bring about a negotiated answer of the ethnic dilemma, which would obviate a troublesome fall-out in Tamil Nadu of a LTTE military defeat. I think that there was a division within the Indian Government on how to deal with the LTTE. I recall that on April 19, 1995, when the LTTE broke the ceasefire and started fighting once more, the Indian Ambassador in Moscow told me that he was not in the least surprised by what had happened. Although he was Advisor on foreign relations to Rajiv Gandhi he had led one thing like five rounds of talks with the LTTE led by Prabhakaran. He had come to the firm and abiding conclusion that Prabhakaran was a psychopath with whom it would by no means ever be feasible to reach a negotiated remedy. Alas, Rajiv G’s pacifist line prevailed in 1987.

Why did President JR succumb to the Indian demand? If there had been any responsible considering on that demand it would have quickly become apparent that the international community would frown on it. How can any sovereign state be denied the correct, or rather the primordial duty, to place down an armed rebellion by military indicates? There would have been collateral damage of course but that could be simply contained, if necessarily with Indian assist, considering the tiny extent of Sri Lankan territory. There was no reason to suspect that there would not be affordable observance of humanitarian standards during the fighting. Considering all that, it would have soon turn out to be apparent that India would not have dared invade Sri Lanka more than that demand. In that occasion it would have incurred widespread international opprobrium, and also it would have grow to be embroiled in a completely messy imbroglio in Sri Lanka.

The explanation for JR’s selection could just be that he committed a monumental blunder. He was undoubtedly a man of massive ability, as shown by the truth that he was the initial South Asian leader to grasp that the State-centric economy could only brig further disaster. But in most approaches his reign brought disaster for Sri Lanka since of his blunders. The question can’t be evaded – whilst acknowledging the possibility of a monumental blunder – regardless of whether he played the role of a traitor in 1987. This question arises since his nationalism has usually been regarded as suspect, as attested by the reality that he was identified for decades as Yankee Dick. There are Sri Lankans who think that in reality he hated the Sinhalese, more particularly the Sinhalese Buddhists, the explanation for which they say is to be discovered in his household history. It is known that in the late nineteenth century and the early decades of the final century the low-country Sinhalese who rose into the elite sought status by marrying into the Kandyan aristocracy. JR’s loved ones was a singular exception.

It is relevant to recall something that reportedly happened at one of Sir John Kotelawala’s well-known egg-hopper breakfasts when he was Prime Minister. JR came to see him on some matter and when he was going away Sir John pointed at him and stated, “That fellow wants to become Prime Minister. If he ever does, he will destroy this country”. The story was recounted to me also by a well-known Sri Lankan – his is a household name – who said that he was present on that occasion. I recall also what was stated by the late Karl Goonewardene, Professor of History, when some horrible injustice perpetrated by the 1977 Government was getting discussed by some of us. It went some thing like this: “The issue genuinely is JR. He hates the folks of this country, and considering that that is so he can only bring disaster to this nation.” I recalled Karl even though the horror of July ’83 was taking place, and I recalled him also while reading the first couple of paragraphs of de Silva’s book.

While the review committee is considering the environmental effects of the CPC, the Unawtuna Beach in Sri Lanka is gaining attention in a far- away country as an example of the adverse effects of building breakwaters along the shoreline. A decision to build a breakwater to resolve beach erosion in the Westmoreland resort in Jamaica has been objected by the Negril Chamber of Commerce using the effects of the breakwater in the Unawatuna beach in Sri Lanka. According to a report appeared in the Jamaica Observer on April 23, 2015.

While the review committee is considering the environmental effects of the CPC, the Unawtuna Beach in Sri Lanka is gaining attention in a far- away country as an example of the adverse effects of building breakwaters along the shoreline. A decision to build a breakwater to resolve beach erosion in the Westmoreland resort in Jamaica has been objected by the Negril Chamber of Commerce using the effects of the breakwater in the Unawatuna beach in Sri Lanka. According to a report appeared in the Jamaica Observer on April 23, 2015. Sirisena came to power in January with an ambitious one hundred-day agenda. We are now nearly a month previous those 100 days. How significantly progress has he produced on his agenda?

Sirisena came to power in January with an ambitious one hundred-day agenda. We are now nearly a month previous those 100 days. How significantly progress has he produced on his agenda?

I will continue to espouse the “Feet to the fire” slogan relative to Mr. W’s bunch whose primary qualification appears to be to have entered that educational institution down Reid Avenue and/or belonged to the traditional Uncle Nephew Party clique of yore. As an aside to this, might I suggest that

I will continue to espouse the “Feet to the fire” slogan relative to Mr. W’s bunch whose primary qualification appears to be to have entered that educational institution down Reid Avenue and/or belonged to the traditional Uncle Nephew Party clique of yore. As an aside to this, might I suggest that

“There absolutely comes a time where a fresh pair of eyes and fresh leadership would be very good. The party has got some fantastic individuals coming up – the Dayasiri Jayasekaras and the Arjuna Ranatungas and the Duminda Dissanayakas. There is lots of talent there. I am surrounded by really good men and women.” the President told his closest advisors after yesterday’s meeting with former President

“There absolutely comes a time where a fresh pair of eyes and fresh leadership would be very good. The party has got some fantastic individuals coming up – the Dayasiri Jayasekaras and the Arjuna Ranatungas and the Duminda Dissanayakas. There is lots of talent there. I am surrounded by really good men and women.” the President told his closest advisors after yesterday’s meeting with former President

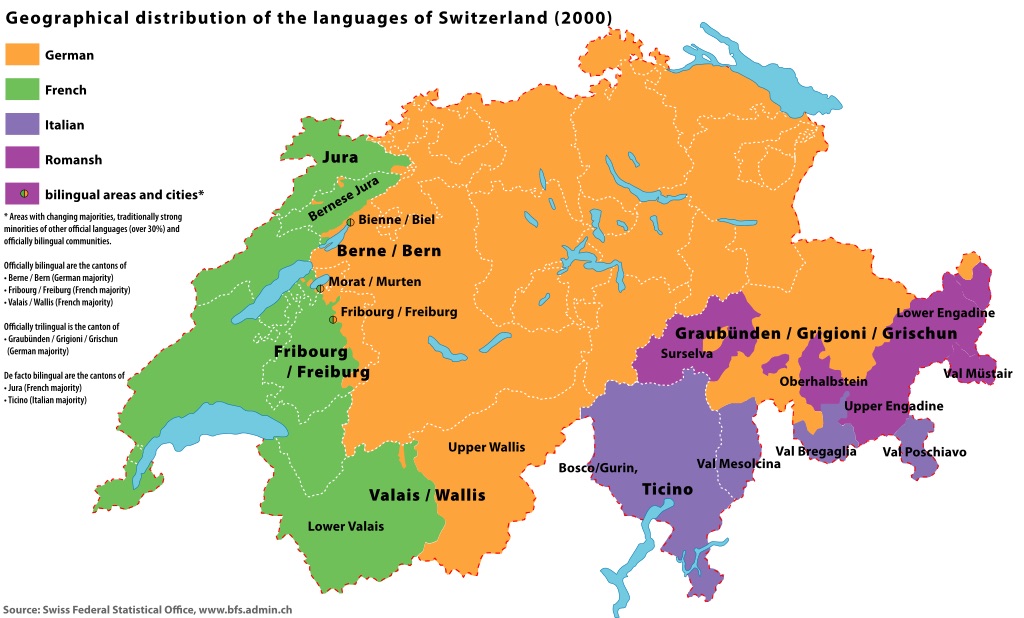

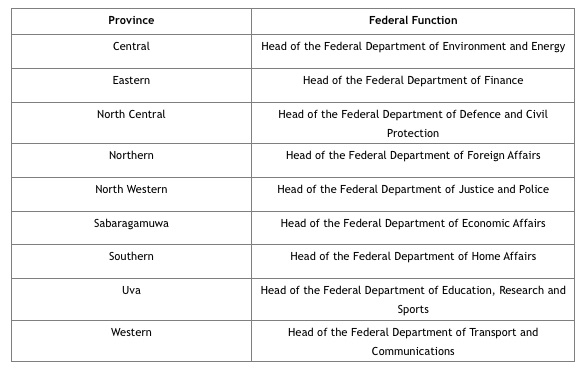

Like in Switzerland, there will be no complete time head of state. Rather the federal council will act collectively as the head of state. Nonetheless, like in Switzerland, due to the national and international need to have for a distinct individual to represent the country, the representational functions of a president will be taken by a single of the members through a yearly rotation system e.g. the Central Province member will be president with the Eastern Province member as Vice President. The following year, the Eastern member will turn out to be president and the North Central member becoming Vice President etc.

Like in Switzerland, there will be no complete time head of state. Rather the federal council will act collectively as the head of state. Nonetheless, like in Switzerland, due to the national and international need to have for a distinct individual to represent the country, the representational functions of a president will be taken by a single of the members through a yearly rotation system e.g. the Central Province member will be president with the Eastern Province member as Vice President. The following year, the Eastern member will turn out to be president and the North Central member becoming Vice President etc.